One of the things I most appreciated about Robin Hobb's The Farseer Trilogy was how it handled prophecy. Seers and sages are hoary tropes in the high-fantasy genre, and the oft-used convention of the prophesied farm boy who grows up to slay an ancient evil has garnered its fair share of ridicule. (Tim Pratt delightfully skewers the trope in his short story "Another End of the Empire," a delightful reading of which is available for free at PodCastle.) Yet even though The Farseer Trilogy hinges on prophecy as does so much fantasy, Hobb manages to make it feel fresh. How? By altering the very nature of the convention.

One of the things I most appreciated about Robin Hobb's The Farseer Trilogy was how it handled prophecy. Seers and sages are hoary tropes in the high-fantasy genre, and the oft-used convention of the prophesied farm boy who grows up to slay an ancient evil has garnered its fair share of ridicule. (Tim Pratt delightfully skewers the trope in his short story "Another End of the Empire," a delightful reading of which is available for free at PodCastle.) Yet even though The Farseer Trilogy hinges on prophecy as does so much fantasy, Hobb manages to make it feel fresh. How? By altering the very nature of the convention.In the series, there's a character known only as the Fool, an acid tongued, albino jester who has the blood of ancient prophets flowing through his veins. Yet the Fool doesn't discern the future as clearly as other more traditional mystic types. Instead of clearly glimpsing what's to come (which we could call "foretelling"), his visions serve as a nexus at which probabilities converge, a central point from which a thousand different futures branch out in a dendritic riot. At one point in Assassin's Quest, the Fool tries to explain it to protagonist FitzChivalry:

"Years ago I had a vision," the Fool observed. ... "I saw a black buck rising from a bed of shining black stone. When first I saw the black walls of Buckkeep rising over the waters, I said to myself, 'Ah, that is what that meant!' Now I see a young bastard whose sigil is a buck walking on a road wrought from black stone. Maybe that is what the dream signified. I don't know. But my dream was duly recorded, and someday, in years to come, wise men will agree as to what it signified. Probably after both you and I are long dead."That's a smart switcheroo and not only because it pleasantly subverts readers' expectations. It also happens to have precedence in at least one of the world's major religions -- Christianity.

While those weaned on the paperback apocalypses of LaHaye and Jenkins might assume that foretelling encompasses the entirety of Christian prophecy, it actually has a trifold nature. Yes, foretelling is part of it, but so is "forthtelling," the idea a prophet speaks moral imperatives for the here and now. However, the third aspect, "typology," might prove the most interesting for genre writers because it's so delightfully different. Francis Foulkes provides a decent starting point for explaining it in his 1959 article "The Acts of God," writing that:

One of the deepest convictions that the prophets and historians of Israel had about the God in whom they trusted, and whose word they believed they were inspired to utter, was that he was not like the gods of other nations ... Rather he had revealed himself to them, and had shown himself to be a God who acted according to principles, principles that would not change as long as the sun and moon endured. They could assume, therefore, that as he had acted in the past, he could and would act in the future.This presupposition forms the foundation for typology. Essentially, an observer can look back at something distinctive that happened in the past ("a type") and see its pattern repeated later on in history ("an antitype"), thus demonstrating divine action by the unchanging God. Examples include the prophet Ezekiel linking Israel's Babylonian exile with its early wanderings in the Sinai wilderness, as well as Jesus pointing out the correspondence of his own forgiveness-securing crucifixion with Moses raising up a molded-bronze serpent for miraculous healing of the people during the Exodus.

Why am I going into such detail? Certainly not to impart some sort of Sunday school lesson (although those really interested in digging into old texts might enjoy G.K. Beale's doorstop-thick tomes on the subject). Rather, I want to urge genre writers toward greater cross-disciplinary study. Many authors brush up on science and history before putting pen to paper; very few study theology, and it shows in their works, with prophecy being just one example. Sure, we have Robin Hobb and Orson Scott Card, Lars Walker and Saladin Ahmed. They put serious thought into the spiritual nature of their fantasy worlds. We need more of them. Our stories -- and readers -- have everything to gain from it.

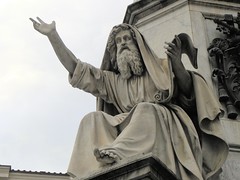

(Picture: CC 2010 by Ian Scott)

No comments:

Post a Comment