Note: The final paragraph of this post contains various spoilers.

Note: The final paragraph of this post contains various spoilers.You know, I really wish writers would kill more of the characters we love.

This sentiment doesn't spring out of a latent sadism or some sort of empathetic deficit, I assure you. Like everyone else who enjoys good stories, I form attachments to particular characters, identifying with them and rooting for their success. When they're in peril, my pulse quickens, my mouth goes dry, and I frantically flip the pages to see how it all will turn out. I'm emotionally invested, in other words. And it's that very investment that makes me believe it's sometimes in a story's best interest for an author to drop the hammer on well-rounded, likeable characters.

To see what happens when storytellers refuse to do so, just consider the action movies of the eighties and nineties. Arnold or Sylvester or Jean-Claude might have faced scored of baddies armed to the teeth and itching to unload them into the heroes' friends and family. Yet the main thrills from such films come not from imminent peril to such folks, but from the inventive dispatching of the antagonists. After all, we know none of the important people will die except the villain and only at the story's precise climax. If someone's going to perish, it'll be a tangential character introduced at an opportune time. It's a simple formula -- and likely the reason why the genre's on life support.

If insulating major characters from meaningful peril cuts dramatic tension off at the knees, placing them before the real possibility of death gives it a growth spurt. In the first section of The Passage, Justin Cronin created a kind widower, carried him through terrible peril and killed him suddenly with radioactive fallout. Justified (aka The Best Show on TV) offed Raylan Givens' aunt with a close-range shotgun blast in a scene that felt like a slap to the face. And Dan Wells' I Am Not a Serial Killer sends one major character to a grisly demise. These stories don't offer impersonal body counts. They serve up white-knuckle reading and viewing because you know precious little is off the narrative table.

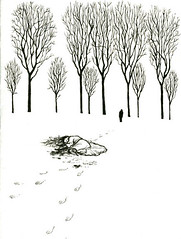

(Picture: CC 2008 by Kurt Komoda)

8 comments:

I take it you would be a fan of George R.R. Martin, then.

In the opening scenes, you are introduced to a lovable kid who loves disobeying his strict, noble parents and climbing adventurously about the castle. In or near chapter 1, he is thrown off a windowsill and paralyzed for life. As the book goes on, you realize this is not an isolated event--actions, even good-hearted and courageous actions, often come with realistic consequences, and sometimes come with shockingly unexpected consequences.

The thing about Martin--and I have no idea how he does this--is that his books truly do celebrate courage and honor. His honorable characters get screwed over by disreputable schemers and often slaughtered for their courage, but they still shine out as the characters you want to emulate. His villains, despite their cleverness, feel two-dimensional in comparison.

I've wanted to read Martin for some time, but I didn't want to dive in before A Dance With Dragons was done. (Apparently, it finally is.) Hate starting a series that remains forever in limbo.

I can sympathize. I'm waiting myself; two more novels need to come out after the current one, and (unlike Robert Jordan) Martin is good at writing prose, so his books are unlikely to benefit by being completed by a more concise author. (A Wheel of Time, however, is better than ever thanks to Brandon Sanderson's comprehension of the purpose of his keyboard's delete key.)

Oh! If you can check it out, "The Hedge Knight" is the most compact and wonderful dose of George R.R. Martin's George R.R. Martin-ness I've found. I read it in the fantasy novella collection Legends 2. It's set in the world of his longer fantasy epic, but as far as I can tell offers no spoilers and deals with no major characters.

(It is also adapted into a comic book, which I haven't read.)

Two more? Aw, no way, man. I just hope he lives long enough to finish them.

You know, Sanderson's involvement in The Wheel of Time rouses some faint interest in me. But I just don't think I could slog through all the books Jordan penned. I couldn't even make it through the first one.

I think I may credit Jordan with some share of my grad-school success. He taught me how to skim, trusting that the average author, in lieu of a good editor and in the absence of a strict commitment to craft, will tell you everything you need to know at least a dozen times, so that you can miss it once and still get most of the effect.

That has stood me in good stead reading /skimming American literary criticism, where the publish-or-perish model often results in books churned out by tired professors who are far more interested in discovering something about their literary objects than honing their craft. Unfortunately, it helps little when encountering French authors, whose obsessively playful attention to the multiple meanings of every word requires one to read them as carefully as a Gene Wolfe story.

I wonder how much of the French criticial playfulness stems from Derrida. He always seemed to know that deconstruction could either lead to despair or a self-imposed, light-hearted silliness with the text.

Your evaluation of the publish-or-perish model seems bang-on to me.

Post a Comment