My wife and I recently decided we should take a break from the ephemera that Hollywood continuously churns out and devote our movie viewing to films with a longer shelf life than the proverbial carton of milk. We printed out The American Film Institute’s list of the 100 best American films of all time and rented the first one neither of us had seen -- The Godfather. I was expecting a thrilling tale full of gunfights and extortion, bodies dumped on lonely roads and lots of Italian-American culture. In other words, all of the archetypes of Mafia crime stories. And Francis Ford Copolla’s epic gave them to me in spades. But it also gave me something I didn’t expect. My wife and I were quiet as the closing credits rolled, and when I asked her what she was thinking, she said, “We just got done watching a tragedy, didn’t we?”

My wife and I recently decided we should take a break from the ephemera that Hollywood continuously churns out and devote our movie viewing to films with a longer shelf life than the proverbial carton of milk. We printed out The American Film Institute’s list of the 100 best American films of all time and rented the first one neither of us had seen -- The Godfather. I was expecting a thrilling tale full of gunfights and extortion, bodies dumped on lonely roads and lots of Italian-American culture. In other words, all of the archetypes of Mafia crime stories. And Francis Ford Copolla’s epic gave them to me in spades. But it also gave me something I didn’t expect. My wife and I were quiet as the closing credits rolled, and when I asked her what she was thinking, she said, “We just got done watching a tragedy, didn’t we?”It may be difficult to think of a story that concludes with the protagonist amassing huge amounts of power, prestige and wealth as a tragedy. But Al Pacino’s Michael Corleone loses his longtime goal of an existence apart from organized crime due to an overweening love of family. It's a love that barely considers the depth of evil in which the objects of its affection are mired. Though Michael thrives outwardly, his hope for a legitimate life traces the descents of Othello, Macbeth and Lear. Only the context changes, soliloquies being replaced by stilettos.

Archetypal critics like to argue that narratives can’t help but fall into such patterns. (See Northrop Frye’s monomyth, on which he claimed one could place the structure of every sort of story.) But while these theorists have interesting insights, they also have a tendency to crowbar texts into artificially narrow readings and a difficult time explaining the existence of noir and horror. No, The Godfather seems to intentionally turn genre’s conventions towards weighty matters of ethics and identity, themes mankind has explored for thousands of years. And why shouldn’t it? Should genre lovers cede the deep things to ivory tower intellectuals just because they happen to like knights and zombies and hard-bitten PIs? No, that’s an offer we must refuse.

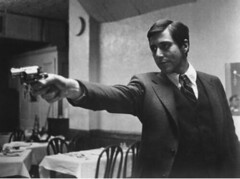

(Picture: CC 2006 by mueredecine)

2 comments:

Interesting point, though I'm not sure you're being entirely fair to Frye.

After all, one of the guys Frye studied most closely, Joseph Conrad, shared a lot of affinities with Noir. It's hard to say that his Marlowe, who constantly searches to stare humanely into the heart of darkness, is all that different from the later Phillip Marlowe.

At the same time, the distinction may break down when one gets to horror. I've been reading some C.L. Moore lately, and came to a realization. Her protagonists, Jirel of Joiry and Northwest Smith, invariably survive their encounters. The stories, therefore, follow the archetypical path of Romance, not tragedy; the protagonist decends (often literally), goes through an ordeal, and returns triumphant. Yet the pleasure I get from the stories is quite akin to the pleasure of reading, say, Lovecraft, whose stories almost invariably end in total slaughter.

Which is to say, perhaps, that the horror genre is determined much more by the atmosphere and imaginative recapitualtion of psychological dreads than on any narrative pattern. (Unlike, say, the Heroic Fantasy or noirish private eye story.)

That could be true about Frye. I certainly don't claim to be any sort of expert on Archetypal theory. Or any literary theory, really. But if noir is (as Peter Rozovsky says) a story in which the protagonist goes willingly to his doom, that doesn't necessarily mean that he has some fatal flaw that undoes him like in classical tragedy. It certainly can. (See The Thief and the Dogs, for example.) But quite a few of such stories seem to feature a poor schmoe being undone by a fatalistic universe. Ditto for horror, at least a lot of it. And while I tend to prefer the sorts of stories that show up on the monomyth, I can't say the ones that don't are immediate failures.

Dunno if that makes any sense at all. But I'm tired, and bed is calling.

Post a Comment